Cancer Survivorship, Collaborations, and the Lessons of a First Time Through

Written by: Thomas Adams - Data Scientist, Data Science Trainer (2019-2020)

Since beginning work at Fred Hutch, I’ve had a series of distinct experiences that seem to follow a common pattern. You might find it familiar: Someone learns about my work at a cancer research center and they share how their life has been touched by cancer.

I’ve heard stories I didn’t know from close friends and intimate details from strangers. Stories of diagnosis and treatment, stories of their own health and of loved ones and teachers and colleagues. A notable aspect of what society calls cancer is that these diseases, taken together, seem to highlight the fragility of all human life. Many of these stories, after all, are punctuated by death and there is no known action or group membership that can guarantee us safety.

But many stories do not end immediately in death. Through the struggle of diagnoses and treatments, many people survive. And far from a tidy statistical binary of 1: alive or 0: dead, life with and after cancer reveals the same remarkable range of human experience present all around us.

So what happens to these survivors? Over the last year, I was fortunate enough to learn something of the work being done by researchers hoping to understand that question. And through the efforts of those researchers and a dedicated group of students, I also got a chance to experience, firsthand, some of the remarkable challenges and rewards that come with one of the great drivers of human progress: collaboration.

It’s my hope in writing this that readers might recognize aspects of their own experiences engaging in collaboration. And I hope also that there will be some who come away with a renewed appreciation for the crucial work done by researchers and clinicians on behalf of cancer survivors. So where to begin the story?

Starting at the End

On Thursday, April 9th, four members of the University of Washington’s Data Science Masters program presented their capstone work to the Fred Hutch researchers responsible for generating their cancer survivorship dataset. Masters students Hallie Ertman, Naman Sharma, Adrian Tullock, and Riley Waters presented to a group composed of Dr. Scott Baker and Dr. Karen Syrjala, their survivorship research collaborators, and others from UW and FHCRC involved in the project.

Insights derived from datasets like these can make dramatic differences in people’s lives. While cancer diagnosis and treatment naturally get a great deal of attention, the burden of the disease does not suddenly disappear following treatment. Cancer survivorship is an area of critical study and it was a remarkable opportunity for the students to engage with such compelling research.

During the presentation, the students were composed and well prepared. Focusing on their delivery and content, it’s not hard to imagine that getting there was simply the result of consistent effort applied with thoughtfulness and intelligence. While it’s no mistake to see such effort, thoughtfulness, and intelligence in their work, there is a bit more of a story to how we all ended up in that virtual presentation room. After all, the first time through anything can be more complicated than we anticipate. And if that first time through involves multiple nonprofit organizations, sensitive health information, remote computing, legacy code…well, it can be a lot more complicated.

Beginning a Partnership

Alliances and partnerships often need time to take form. While the students started work on the project in early fall 2019, the path to the collaboration began at least a half year earlier in the spring of 2019. Dr. Carly Strasser, Fred Hutch Director of Data Alliances and Strategy, learned about the young UW program (UW MSDS), then producing some of the first graduates of a rigorous data science curriculum and looking to partner with organizations who could provide datasets for students creating capstone projects. Carly found an ideal match after approaching Drs. Baker and Syrjala, directors of Fred Hutch’s Survivorship Program. Under research protocol 2550, the program had for years been gathering patient data within their Survivorship Information Management System (SIMS) with the aims of understanding and improving long term health outcomes of cancer survivors. As we learned speaking with Scott and Karen, the data had been used extensively to help clinicians working with patients, but had not yet been probed as thoroughly for the purposes of statistical analysis.

Seeing an opportunity to forge a beneficial partnership with UW while furthering important research at Fred Hutch, Carly assigned the task of heading the project to me, then recently arrived as a data scientist and trainer with the Coop Bioinformatics and Data Science Cooperative. I worked with members of the Survivorship Program and leaders of the MSDS to craft and submit a proposal for Fred Hutch to be a capstone sponsor using the SIMS dataset. Our proposal and the chance to work with Fred Hutch were apparently appealing enough to garner significant interest from program students. Ultimately Hallie, Naman, Adrian, and Riley were the four selected for the project.

A Slog to the Starting Line

This all was happening back when meeting people face to face was still a thing, so I was able to gather with the students at UW and later at Fred Hutch to start figuring out what we would all need to do. Meeting Adrian, Hallie, Riley, and Naman, I was impressed by the range of experiences they were bringing to the program as well as their ability to focus in on specific tasks while developing a picture of the whole. It turned out to be a good thing that we had such a strong group, because the project faced significant logistical challenges at nearly every stage.

The data themselves were highly sensitive, composed of detailed survey responses from cancer survivors as well as associated electronic medical records (EMR) collected by clinicians. While the Fred Hutchinson employees involved were able to legally access the raw protocol 2550 data under the supervision of Drs. Baker and Syrjala, the students would need to be onboarded and trained as non-employee affiliates of the center. Additionally, they could not begin working with the dataset until it had been thoroughly de-identified and stripped of all unnecessary personally identifiable information and protected health information (PII and PHI). Emily Jo Rajotte Artim, study manager for protocol 2550, helped us access the appropriate EMR. Meanwhile, I was working closely with Emily Silgard and Peter Amundson, both from the Hutch Data Commonwealth, to navigate the SIMS database and de-identify the results of our queries, a process made more complicated by the fact that many of the key folks who had coded up the SIMS system were no longer working at the center.

Even properly de-identified, however, there remained the question of where to store and work with the still sensitive data, since the students did not have physical access to computers subject to the center’s encryption and other measures to prevent data breaches. Carly and I worked with regulatory experts at the center, the Hutch Office of General Counsel, and a number of database, EMR, and scientific computing specialists to execute a plan for the students to have remote access to data storage and computational resources while honoring legal and ethical obligations to protect the sensitive information of the patients involved. So far so good.

Seeing People in the Data

After weeks of consultations, training, data and infrastructure prep, and document wrangling, the students were finally able to begin working directly with the data and connecting it with the metadata they had already been exploring. But even with full access to the de-identified data, they were facing new challenges. At issue was the significant complexity of a dataset concerning a vast array of cancers and covering a dizzying range of metrics for behaviors, characteristics, and quality of life among the cancer survivors.

Understanding the data and preparing them for statistical analysis and modeling were enormous tasks. Looking closely at the dataset, there was no missing the richness and potential. Also apparent to us, however, was how the design reflected a primary focus on supporting clinicians trying to directly improve cancer survivor outcomes, not on statistical analysis. It’s somewhat of a truism in data science to say that most of your time will be spent on data exploration, cleaning, feature engineering, and other preparation. If you’re ready to start fitting and evaluating machine learning models, for instance, you’ve already made tremendous progress. This project certainly bore that out, even following significant work by a number of people to get the data ready for the students.

But another dimension of the data struck me more than I had anticipated as I explored the files with the students. Among the many factual fields with survivor responses to categorical and numeric questions, there were a number of fields which encouraged patients to provide additional information that might be useful to clinicians. There, separated from names or identifiable details, were brief accounts of survivor experiences, in their own words. Small topical vignettes about pain or depression, weight loss or gain, concerns about sexual function, descriptions of stress in personal relationships, challenges returning to work. I would guess that most everyone living in the world of disease research prepares to encounter the human face of these diseases, even those whose research isn’t directly patient facing. But I was caught off guard. I did not expect supplemental text fields to evoke such vivid pictures of human lives.

I imagined what descriptions would have come from my grandmother, Vinka Mijić, whose life was prolonged by a double mastectomy in 1950s Yugoslavia, but who suffered for the remainder of her long life from the lingering effects of the harsh treatments that probably saved her. Strange to be fully immersed in the analytical part of my mind only to be suddenly reminded of my remarkable grandmother. And powerful to recognize that every row of our dataset represented another such life. How were doctors and researchers in Baka Vinka’s era considering her life as a cancer survivor?

Progress and Direction

With such a broad set of features, the students divided the data into sections to explore and prepare independently or in pairs, coming together regularly to compare work and findings. The students expressed excitement at the chance to contribute to research that might improve people’s lives, writing about their purpose “…to gain analytical insights that may improve the clinical process for cancer patients and better understand how cancer affects their lives.”

Having preliminary work completed and a number of promising directions to explore further, we arranged for the group to meet with the SIMS team at Fred Hutch to share progress and get feedback on which directions were of the greatest interest to Drs. Baker and Syrjala and other collaborators in the Survivorship Program. Scott, Karen, and their team were generous with their time and gracious in responding to the students’ proposal, offering specific suggestions and asking helpful questions. Of particular interest to the researchers was work that might later facilitate future statistical analyses.

Ultimately, the masters students chose to focus on a few related questions:

- Can quality of life indicators be accurately predicted using the survey data?

- What associations can be found between patient characteristics and health behaviors?

- What common trends exist when comparing the baseline and follow-up surveys?

Using a variety of statistical modeling approaches and having identified or crafted a number of relevant features from the data, the students set about trying to explore their chosen questions. They built out a pipeline that would map responses from the surveys to usable data tables where they could be merged with appropriate information from the medical records. Crucially, they worked hard to incorporate structures and careful documentation which would help their efforts to generalize, meaning that later explorations of these same data would be easier and more reproducible.

Capturing feature correlations with quality of life metrics, choosing how to select features for model fitting while mitigating multicollinearity, and evaluating a number of modeling approaches, the team settled in the end on an implementation of a random forest model, citing “…the model’s ability to handle hundreds of predictor variables and determine feature importance via mean decrease in impurity” among a number of other factors. While none of their models was unambiguously the strongest, compared against their other, competing models, the students found that their final random forest approach yielded the best performance predicting outcome variables such as patient responses concerning depression and others.

And yes, we did discuss just how misleading it can be to rely on the term “feature importance” when communicating with people about fitted models. But more than anything, we discussed how the students’ work could best serve not just the immediate questions at hand, but also later questions not yet explored or even asked. We began to consider a broader notion of our collaboration, one that would include future unknown partners and reap the benefits of groundwork begun now. The deliverables for this project would include the power to make future projects more fruitful themselves.

Results and the Future

With such a challenging dataset and problem space, no one involved in the project was expecting the results to be tidy or simple. In their report on the project, the students focused on the future value of their work, writing, “The biggest challenges with the SIMS data are the knowledge barrier for the clinical data and the structure of the raw survey-related data. The significant amount of work that has gone into creating the data pipeline, data mapping, and reproducible analyses will be useful tools in generating more key insights from the SIMS data.”

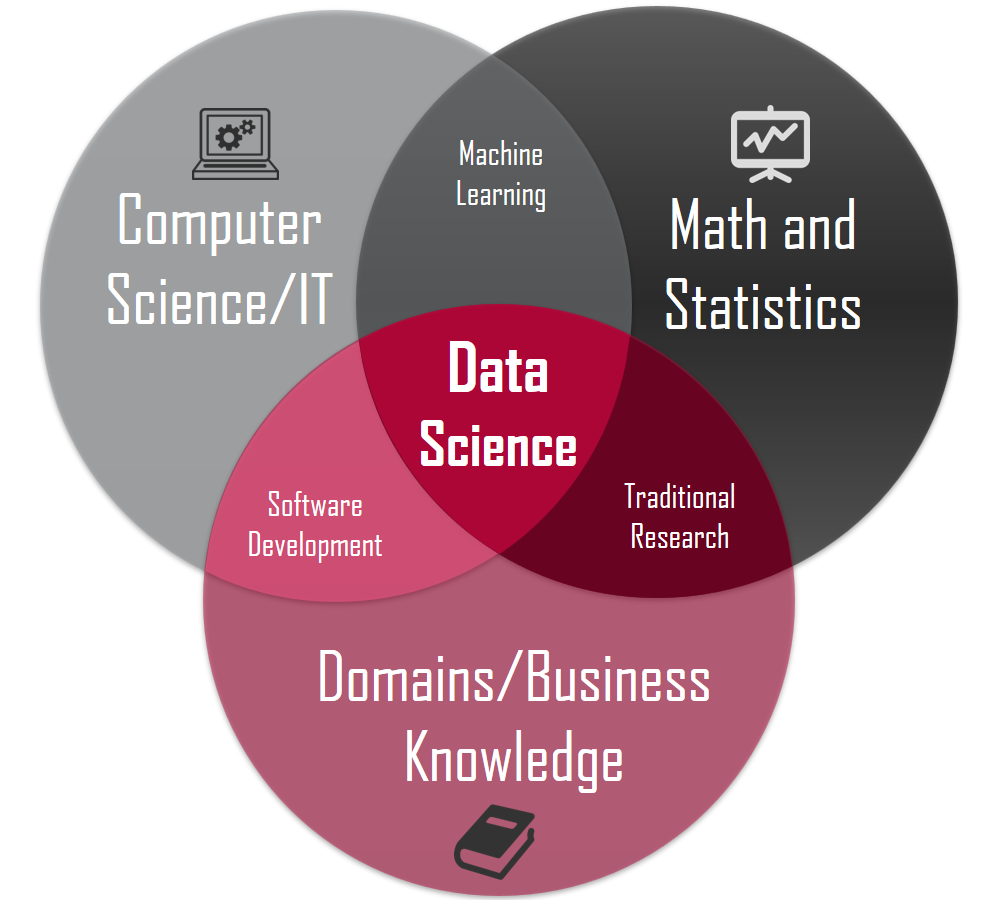

Reading the students’ description, I noted their emphasis on knowledge of clinical data. There is a canonical structure to images used when defining “data science.” If you’ve done reading on data science, you might have seen it. I took this one from Towards Data Science

There are plenty of variations, but that structure generally puts “data science” at the central intersection of a Venn diagram of Math/Statistics, Computing/Code, and Domain Knowledge. The implication of that last circle is important: If a data scientist doesn’t know enough about the specific domain where she is working, how can she expect to understand and evaluate the implications of her choices, assumptions, and results? There are plenty of wrong choices in data science, but “wrong” isn’t really at the crux. Instead, most choices, assumptions, and results are wrong/right/wise/foolish/meaningful/etc. within the context of a specific domain. If you’re forced to make choices without the benefit of appropriate domain knowledge, it’s fair to say that you are, at least to an extent, flying blind.

Nonetheless, the students were still able to outline findings “…that yield valuable information about the survivorship program” concerning a number of factors such as depression, fatigue, and pain. They summarized cautiously, saying that a “limited longitudinal analysis of the patient responses” suggested that “the patients are largely walking away from the treatments educated about their plans and health, and are not experiencing notable detriments to their perceived quality of life.”

Speaking informally on behalf of the student group, Adrian Tullock wrote, “We definitely want to thank everyone who worked to make this entire experience possible and appreciate that we got to work with some great people at Fred Hutch. As a team, we would love to have done more, but I’m confident we’ve built a solid foundation for the next group to build from.”

Commenting on the collaboration, Drs. Syrjala and Baker added, “We were amazed by the determination and dedication that the student’s put into this capstone project. Having never been involved in anything like this before we didn’t really know what to expect. We provided the students with a large and complex dataset which had many inherent flaws in how it was structured. They took that and methodically explored, organized, mapped and ultimately analyzed the data exploring the kinds of questions that we have hoped the data would be able to be used for when we started collecting it nearly 10 years ago. The ultimate benefit of this work will be to cancer survivors, including those who graciously agree to fill out our surveys and provide the data so work like this can continue.”

Among those in attendance for the final presentation was Dr. Megan Hazen, Capstone Director for the MSDS program. Dr. Hazen voiced enthusiasm for the students’ experience working with Fred Hutch and expressed her desire that the center and UW MSDS continue their collaboration into the future, saying “I do hope we’ll be able to repeat the experience next year.”

For my part, I came away from the project inspired by the work being done on behalf of cancer survivors by Scott, Karen, and their collaborators. I was grateful for the chance to work with Hallie, Naman, Adrian, and Riley and impressed by their ability to dive into such a complicated problem space and craft something useful and insightful. And I came away with a more concrete appreciation for how complex it can be to navigate legal, ethical, and logistical challenges before even getting to the parts of a project we would normally think of as data science.

So what about future collaborations of this type? I don’t think anyone pretends that next time will suddenly be easy. Still, we learned a lot working past missteps and deadends in this first effort. Equipped with those lessons, I think that next time–whatever its form–might well be easier. After all, it won’t be the first time through.

Relevant links:

UW Master of Science in Data Science program (MSDS)

Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center Survivorship Program

The Coop Bioinformatics and Data Science Cooperative

Those at Fred Hutch hoping to explore a future collaboration with the UW MSDS should contact Dr. Kate Hertweck, training manager for the Coop:

khertwec at fredhutch.org

Those interested in the capstone group’s final report or other related materials should contact Dr. Scott Baker or Dr. Karen Syrjala, directors of the Survivorship Program:

ksbaker at fredhutch.org or

ksyrjala at fredhutch.org

To contact the author of this write-up or inquire about contacting the MSDS students, please write to Thomas Adams:

tadams at fredhutch.org or

thomas.harlan.adams at gmail.com